Ancient cultures believed that human creativity and divinity were related. That the gods worked through us whenever we fashioned a poem, a dance, a painting, a piece of music, or an invention. How can we get that perspective back?

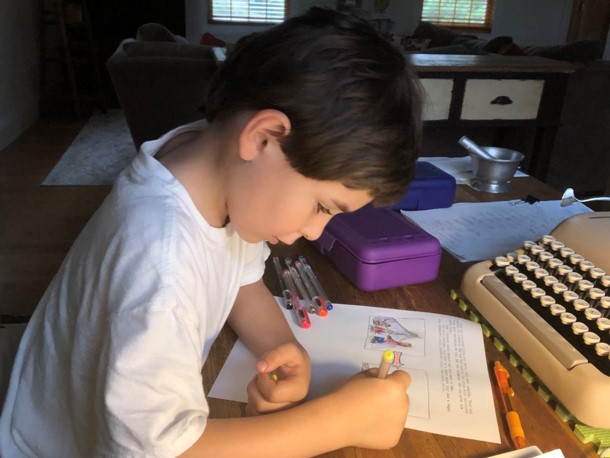

My son, Ethan, is seven-and-a-half years old.

He looks disturbingly like I did at that age. The same tousled brown hair. The same flashing brown eyes. The smiles that melt quickly to frowns, then twist themselves back into grins in a third of a second.

Whenever I behold my son’s molten facial expressions, I recall the word mercurial: “characterized by rapid and unpredictable changeableness of mood; having qualities of eloquence, ingenuity, or thievishness attributed to the god Mercury.”

Mercury, as you likely recall, was the messenger of the Roman pantheon.

He was always portrayed as a youth equipped with winged shoes and wings on his helmet. His job was to zip back and forth between the more prominent gods, such as Jupiter, Hera, Venus, Ares, and Minerva.

Mercury carried dispatches. But, while coursing along his routes, he made plenty of mischief. He often played tricks on the gods (the same way Ethan plays tricks on me). And, since Mercury was also the god of thieves, he also — frequently — stole things from them.

Before he became Romanized, Mercury was called Hermes by the Greeks.

Here’s a thought experiment. Let’s try to imagine a time before monotheism … a time when Western peoples believed in multiple deities who manifested themselves in common things.

During this era, creativity and divinity were essentially seen as expressions of each other.

Viewed through this lens, it’s easy to see how my young son’s facial expressions were once quite commonly seen as divine. As was his birthright — the child’s innate tendency to create.

In fact, of Hermes, the poet Robert Bly writes:

“[He] is the god of the interior nervous system. His presence amounts to heavenly wit. When we are in Hermes’ field, messages pass with fantastic speed between the brain and the fingertips, between the heart and the tear ducts, between the genitals and the eyes, between the part of us that suffers and the part of us that laughs. Hermes is Mercury, and we know that mercury cannot be held in the hand — it rolls everywhere, separates into tiny drops, joins again, falls on the floor, rolls under the table, moves with amazing quickness. It is correctly called quicksilver.” (Iron John: A Book About Men, pgs. 151 – 152)

These are apt comparisons.

Robert Bly and my son have never met. All the same, Bly’s words perfectly describe my boy’s innate nature.

Watching a seven-year-old process emotions is like watching a film reel zipping through fast forward.

Their young brains don’t get stuck on much. They haven’t yet learned the adult’s bad habit of taking things personally — most especially, ourselves.

As I’ve already shared in this blog, we adults cherish the egos we’ve carefully nurtured for ourselves. We wear our egos as masks because we believe our masks can protect us from the slings and arrows of life’s outrageous fortune.

(They can’t, of course. Nothing can. In fact, in so many ways, this sort of surrender to life — the moment-to-moment practice of acceptance — marks the start of the road to wisdom.)

Most of us have worn our masks for so long, we don’t really recognize them anymore. Each time we look in the mirror, we figure that strange person staring back at us from the glass is really us.

But of course it’s not. It’s the ‘us’ we’ve chosen to be. The ‘us’ we long ago crafted to deal with the world.

Therein lies our dilemma.

Our masks hold no creative power. That power — the power of creativity and divinity — is only wielded by the person hiding beneath the mask.

Which is why, to recover our sense of creativity and divinity — to recapture our power to paint, to write, to draw, to dance, to sing, and to make — we must be willing to doff our masks and return to that state of wonder which we all knew when we were children.

This is not my idea. Great thinkers throughout the ages have expressed this dynamic in many ways.

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities,” wrote Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki, “but in the expert’s mind there are few.”

The French novelist Alexandre Dumas once put it like this: “How is it that little children are so intelligent and men so stupid? It must be education that does it.”

You can also find this sentiment in the Christian Book of Matthew (18:3): “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

My son has not yet donned his mask, which is why his eyes light up balls of witch-fire when he’s excited. He has yet to surrender his creativity and divinity to the humdrum expectations of our ordered, polite society.

There’s still something magical about Ethan. His brain zips this way and that with ideas. His emotions swell fast in his tiny bird chest and dissipate just as quickly.

Physically, he comports himself like an amateur hobbit gymnast doing a floor routine on methamphetamines.

His world right now is a Shangri-la of Star Wars action figures, Pokémon trading cards, birthday parties, Friday night pizza, and all the mystical secrets offered by girls who chase him on playgrounds, and his multiplication tables.

I have days where just watching him leaves me equally amazed and exhausted. His antics often prompt me to think of myself when I was eight years old. Doing this fills me with equal parts nostalgia and fear.

Nostalgia for how we all used to be at that age.

Fear that someone will try and wrest Ethan’s creativity and divinity away from him.

As John Lennon once said: “every child is an artist until he’s told he’s not an artist.”

Let’s remember to tell our children they’re artists.

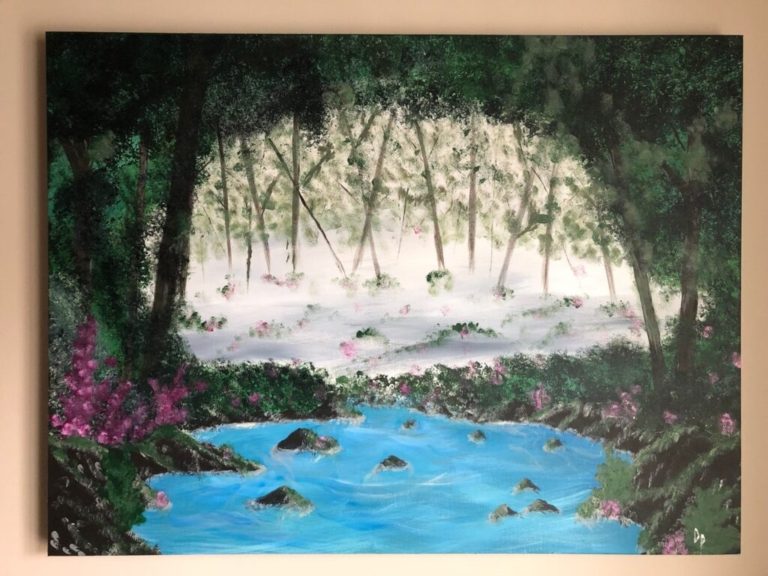

What they make doesn’t matter. It might be a painting, a story, a house, a family, or a business.

What matters is that they remember they can create, create, create.

The same goes for you and me, of course.

We are all, in our hearts, little children.

Damon DiMarco